JAN

The Value of Selling Steer Calves vs. Bull Calves

University of Kentucky College of Agriculture, Food and Environment

LEXINGTON, Ky. (January 29, 2018) — One of the more common questions that I get as I travel the state involves the magnitude of the price premium for steers over bulls. Most agree that steers will outsell bulls of similar weight, but it is also well established that castrating bulls requires time and some expense. Further, it is generally accepted that bulls will outgain steers, which further complicates the discussion. While there is no way that this short article can completely address this topic, it should help provide a framework to help producers make this basic management decision.

We will start with the basic notion of price differentials, and even this is not completely without question. I will occasionally get a call or email asking why bulls are outselling steers at a given time or location. The first thing to understand is that there are thousands of cattle sold at Kentucky markets every single day. Inevitably, a group of bulls will outsell a group of steers on occasion. Sometimes this may be due to quality factors, other times it might be a lot size issue, and it can sometimes be due to the needs of individual buyers at a given time. However, these instances are the exception, rather than the rule. This can be best shown by examining actual price data collected by Kentucky market reporters.

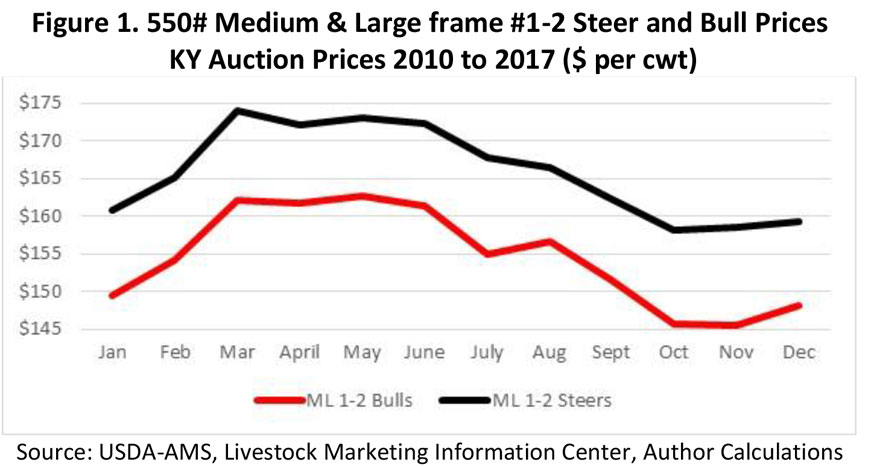

Figure 1 shows prices for 550 lb. steers and bulls in Kentucky auction markets from 2010 to 2017, by month. To compile this data, I averaged the 500 to 550 lb. weight range with the 550 to 600 lb. weight range for all state auctions. This excluded cattle that market reporters identified as value-added, fancy, thin, fleshy, or otherwise noted as falling outside the norm. Utilizing the eight years of data available allows us to take a longer term view on this question. Note that over the 8-year period depicted in figure 1, steers outsold bulls by a little over $11 per cwt. It may also be worth noting that the 550# steer price exceeded the 550# bull price in each of the 96 months analyzed. Again, that doesn’t mean that every single steer lot outsold every single bull lot, but it does mean that on-average, steers consistently outsold bulls.

Now, one limitation of comparing prices, as in Figure 1, is that it compares steers and bulls of the same weight. For example, an $11 per cwt price differential on a 550 lb. calf is over $60 per head. Clearly, this ignores potential weight differences between the two. So, how much more would that bull calf have to weigh to bring as much per head? This answer is not as simple as one might think because of price slides. As calves gain weight, their value per cwt decreases. This is a key concept in cattle marketing that impacts most all decisions that producers make. Let’s walk through it step-by-step.

The average value of a 550 lb. bull calf from 2010 to 2017 in Kentucky auction markets was $853 (550 lb. @ $155 per cwt). A price slide of $15 per cwt would mean that for each 100 lb. increase in the bull’s weight, his price decreases by $15 per cwt. So if a bull weighed 600 lbs., rather than 550, his price would have most likely been $147.50 per cwt ($7.50 per cwt less). This would place the value of the 600 lb. bull at $885 (600 lbs. @ $147.50). This is $32 more dollars than the 550 lb. bull, but only about half of the additional $60 needed to make him as valuable as the 550 lb. steer calf. So, an additional 50 lbs. of weight is not likely to be enough to make up for the price discount that bulls see relative to steers, assuming a pride slide of $15 per cwt.

Probably the most valuable use of this approach is to use it as a way to value additional lbs. In the previous scenario, an additional 50 lbs. added $32 of value to the bull on a per head basis using a $15 per cwt price slide. This means that those additional pounds were worth roughly $0.64 each. At that rate, the bull’s weight would need to exceed the weight of the steer by 94 lbs. for their values to be similar. Using a smaller price slide of $10 per cwt, would make the value of those additional lbs. worth about $0.94, which would mean that the bull would need to outweigh the steer by roughly 64 lbs. for his value to be comparable. This discussion is quickly summarized in Table 1.

The final point that needs to be made here involves implants. Implanted steers have the potential to gain as efficiently as bulls, especially if castrated early. This may allow for comparable sale weights at steer prices. Again, I am fully aware that working calves takes time and facilities, but if a producer does choose to castrate their bulls, implanting does provide another option for producers that are not targeting a market that prohibits their use.

The purpose of the previous discussion was primarily to make two points. First, there is solid evidence that bulls will sell at a considerable discount to steers in Kentucky auctions. Second, it would require significantly higher sale weights for bulls to offset this price discount. Still, there may be reasons such as time limitations, working facilities, or other factors that may result in a producer choosing not to castrate bulls. However, one should also understand that there are individuals in the market place who make money by purchasing bulls, castrating them, backgrounding them for a period of time, and re-selling them. Producers who typically sell bulls may want to consider the potential value that can be added to their calves through this practice as they look for ways to increase profitability in the future.